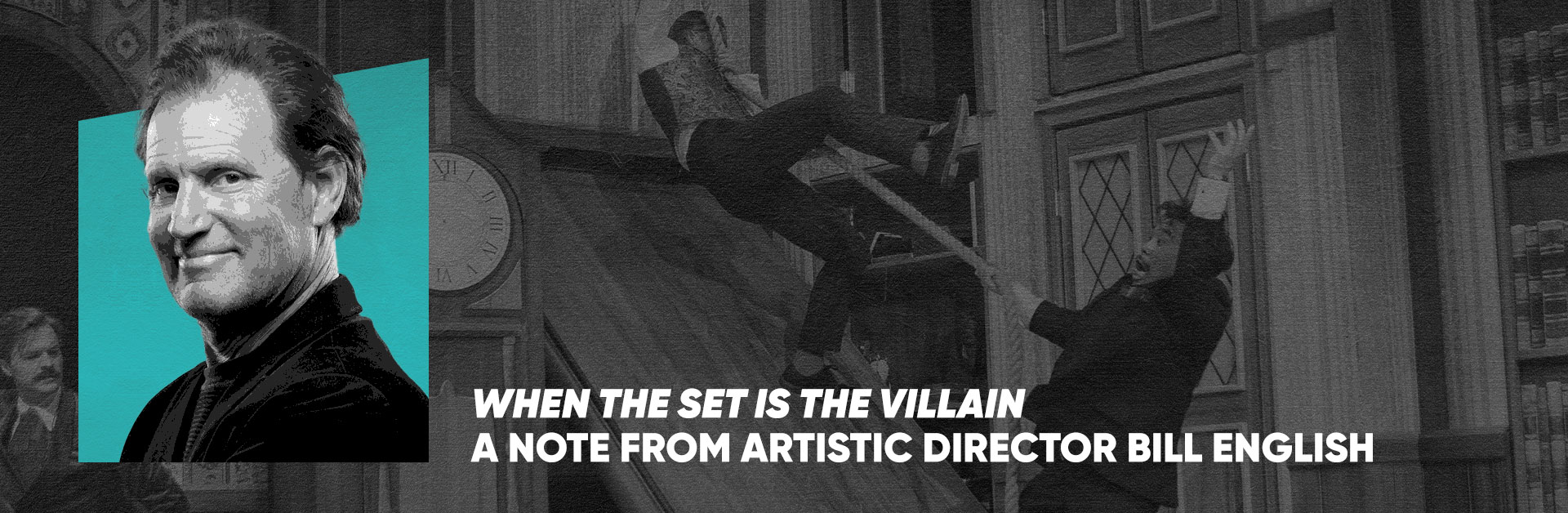

Working for many years as a set designer, I have never imagined that scenic art could be the villain of a story. But watching The Play That Goes Wrong has made us all aware that the environment on stage can be the primary antagonist. Boobytraps lie in wait for every character, and the more wary the actors become, the more insidious the sabotage. It is as if there is a nefarious intelligence intent on reminding complacent humans that nothing in their environment can be trusted; no doorknob, chair, barometer, balcony or wall can be relied on to perform its expected function.

There is a universal truth hiding inside the silly farce, a metaphysical terror that we all understand as we grip our armrests waiting for the next catastrophe. We learn in theatre class that the given circumstances are everything – how the protagonist came to this point in their lives, what environmental and family elements conspired to put the character into an impossible quandary. In that way, the set or the environment is always a pivotal character in the drama! The actors cannot control it. It shifts effortlessly from place to place and time to time, as out-of-control as the weather. And we wonder, can the humans in the story overcome it? Adjust to fit within it? Or flail away, hoping they can change it?

Adam Griffith and the cast of The Play That Goes Wrong (2024) as the set falls down around them.

Early in our history at the Playhouse, we produced Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train by Stephen Adly Guirgis. Blessed to star the great Carl Lumbly alongside a young actor on the rise, Daveed Diggs, the play took place in an exercise yard at Rikers Island prison compound. The characters, a born-again serial killer and a young kid who had shot a cult leader for brainwashing his best friend. They meet, locked into separate chain-link chambers, as the “saved” murderer tries to help the kid take responsibility for his actions.

Here is an extreme example of how the set as enemy. Both are caged – one for terrible crimes, the other for a less-heinous act of revenge. Both battle being defined by their imprisonment. The murderer (Lumbly) seeks to escape by putting his faith in a forgiving God. But in the end, his faith fails him, and he goes to his execution, groveling in terror. The young first-time offender (Diggs) finally finds spiritual freedom by accepting responsibility for what he has done, despite the consequences. It was important that the set symbolize their captivity, with only glimmers of a view coming through slits in their concrete and chain-link containment.

Carl Lumbly, Gabriel Marin, and Daveed Diggs in ‘Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train’ (2007).

In The Nether, the set designed by Nina Ball was a four-sided spinning nightmare: an interrogation room, a parlor and a bedroom in an antebellum mansion dream world where virtual child molesters could act out their fantasies, and a field of dreams where the perpetrator of the hall of mirrors could imagine himself the hero of the story. For our production, we literally turned off the running lights in the theatre and covered our exit lights with dimly lit versions so the audience would be plunged into black terror as our whirling chamber of horrors spun.

How was the set a villain? It created the seductive illusion that men with harmful intentions towards children could act out their impulses without consequences, without facing themselves, without committing to change. The addictive power of the environment was impossible to resist, tantalizing and gratifying their desires in a fictional world rather than facing themselves in reality. And when the make-believe chamber of horrors collapses around him, like in The Play That Goes Wrong, our protagonist is left with nothing.

Louis Parnell, Warren David Keith, Josh Schell, Matilda Holtz, and Carmen Steele in ‘The Nether’ (2016).

One of our most fun sets was for Colossal, which put a football field on our stage. With goal posts, grass, chalk lines and a scoreboard, this seemingly neutral environment set the stage for a unique coming-of-age story. A young gay man, torn between dance and football, suffers a crippling injury as he throws himself in front of another young player to save him from being injured. As he struggles to find himself, the gridiron looms in the background, a taunting reminder of the standards of manhood and success that will never serve him.

He must watch himself be crushed on the playing field over and over until he can face the truth about himself and be honest with his father about who he is. The field itself represents values and standards that will never support him. They loom over the drama like the villain until he is able to overcome them.

The cast of ‘Colossal’ (2016).

In life and in the theatre, our environment comes with rules against which we judge ourselves, standards we will never be able to meet, walls we must push out of our way, doors that must be opened. The physical world on stage represents boundaries imposed by society or ourselves against which we must push in order to grow. And even in the silliness of The Play That Goes Wrong, there is a triumph of the spirit for the human impulse to make things work against all odds.

– Bill English, Artistic Director

The play was a total hoot. Sometimes just laughing can cleanse the soul; mine came out spotless frim the constant laughing at the great timing the actors put into making this farse SO SO good. Thanks so much.