May, 2016 Newsletter

Bill English, Artistic Director

When I was thirteen, under the influence of Errol Flynn and Burt Lancaster, I was determined to become a swash-buckling movie daredevil. Our Junior High School had recently built a one-story temporary structure that intruded into what was formerly playground space. My fellow seventh-grade classmates, always at war against teen boredom, quickly realized that a tree near the new structure afforded a way onto its roof, and soon a collection of us congregated up there, sheltered from the prying eyes of the schoolyard monitors by the branches of our convenient tree. And from that hidden rooftop, we plotted the overthrow of the universe.

A mere six feet away from this new building beckoned a six-foot high, four-foot wide chin-up bar, a remnant from the play yard. Having already earned the honorable title of “Monkey Man” by rescuing a basketball stuck high in the rafters over our gym, I was obsessed with staging a new, more impressive exploit. Then, one day on the rooftop, my eyes seized upon the nearby chin up bar. I convinced myself that it would be possible to leap from the edge of the roof of the new building, catch my hands on the bar, swing out like Tarzan, and then gracefully drop to the ground, landing victoriously on my feet.

I diligently studied the logistics of this the leap for days, and then I announced to my fellow rooftop-dwellers that after school, on the upcoming Friday, I would attempt this great feat. Everyone eagerly gathered at the appointed time, and after a suitably suspenseful pause – filled with the imagined drum rolls and gasps from the crowd – I took the leap. I had gauged the distance perfectly, and my hands landed precisely as I had planned, directly on the bar. A brief moment of elation. But what I had failed to consider was the significant centrifugal force my thirteen-year-old body would yield when swinging at full momentum in an arc. Combined with my weight, my arms were not nearly strong enough to withstand the force. My hands slipped off the bar, just as my body swung fully out, completely parallel to the ground. I felt suspended up there, six feet in the air, for a small eternity, and then I catastrophically crashed to the ground. After a few moments of unconsciousness, I came to, gasping for the breath knocked out of me.

As I gradually regained awareness of who and where I was, I realized that the motley adolescent crew around me was whistling, whooping, and cheering madly. I was baffled by their uproarious reaction: why were they so thrilled and excited by my abject failure? Why were they cheering instead of taunting and mocking me? Once we confirmed that I had miraculously broken no bones, my elated peers lifted me up off the ground, each one reaching out to touch me with enthusiastic pats on my shoulders, head, and back. They whisked me off to Woolworth’s for celebratory malts. And that is when I first learned the transformative power of taking risks.

I think back to that time now as I have been torturing myself for months over selecting a new season, a time when my life is defined by “risk.” I consider producing theatre to be one of the riskiest professions, reasonably comparable to betting on race horses. In horse betting, you make educated guesses based on various information acquired by studying each horse: her lineage, her training, her performance record, and her jockey. But which horse will actually win? No one really knows, especially given such unpredictable factors such as wind, moods, and field conditions.

Accurately predicting how well a theater season will succeed is similarly subject to a host of capricious factors: What does the public really want to see? How will the many elements of a production actually fold together? How will the assigned critic on a particular day, in a given mood, react to the subject of a play? At best, this business of theatre involves highly educated guess work; there is no sure thing. And no one can predict how any specific season will fare. Somewhat like the unpredictable chances of a thirteen-year old monkey man defying gravity with a chin-up bar.

Clearly, I have been drawn to a life of risk, a life of educated gambles. Has it been just for the adrenaline rush? Or is there something about art and risk that are inseparable? We professional story tellers are a compulsive lot. We may not know why, but we simply can’t “not” tell them. We are determined to affect people with the magical power of stories. We are addicted to lifting up spirits, changing opinions, challenging prejudices, transforming lives.

But people do not always want their spirits lifted, their prejudices challenged, their lives changed. And even when they do want that, a particular story may not resonate with the audience for a variety of reasons: weak writing, poor direction, unimaginative performances. And so the play flops. We fail.

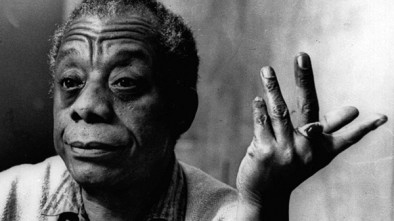

James Baldwin wrote on the subject of creating art: “[It] is not an investment. It is not a day at the bargain counter. It is a total risk of everything, of you and who you think you are, who you think you’d like to be, where you think you’d like to go – everything, and this forever, forever.” In my first college acting class, the jaded professor said, “If you can do anything else[besides acting], do THAT!” He was warning us dreamers and poets, trying to wake us up to the enormous risk inherent in pursuing an artistic life, where failure would be the norm. Why would we want to follow such a difficult, unpredictable path? The only answer that makes sense to me, of why it is even worth the trouble: to lift people up, to challenge beliefs, to effect positive change.

I doubt that I had any such grand aspirations as I crouched at the edge of the roof that day so long ago, my skeptical peers glaring up at me. But I think of that moment now when the wind gets knocked out of me by a bad review, and I am gasping for spiritual breath. I remember my cheering classmates applauding me, despite my failure to execute my intended swash-buckling maneuver. I know that like my seventh-grade peers, our theatre patrons cheer us on the most when we take that grand leap and risk it all.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Please feel free to leave your comments below.

Best,

Bill

Thanks for your insights, Bill.

My partner and I recently walked out of San Jose Opera’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire. We were wondering what they were thinking producing a show so degrading to women, (and men, too) in this time, in this place. There were no great sets to enhance it. The orchestra on stage was a distraction. The score was a disappointment.

It is helpful to see that you struggle with how to meet the varied tastes and preferences of the audience. We are blessed to be a varied lot in the Bay Area. Thanks for taking the risks to reach us.

As usual, you tell amazing stories! What a joy this one was. I’m glad to survived the leap! And the theater!

Bill,

Your betting the horses analogy might be extended. More than one lifelong daily better I have know has explained that one never automatically bets the horse most likely to win, to win. They do the analysis you mentioned, but just as a preliminary, as groundwork.

Rather, the crucial input is the context of the betting crowd–as it shows up in the odds. What one does is determine one’s own odds for each horse finishing in all the possible places. But only bet when the crowd has mispriced something badly. That is your advantage. For example, in a race with a heavy favorite, a horse that could never win but could easily place or show may be neglected; the resulting odds may be “too high” against those conclusions simply as a matter of neglect by bettors.

What’s the theatre analogy? The no-name playwright whose voice fits the times world premier? A comeback play by a fading star? A surprising casting choice? Or a second leap to the monkey bar with an accommodation for centrifugal force??? You tell us!